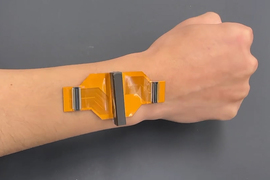

MIT engineers have developed a small ultrasound sticker that can monitor the stiffness of organs deep inside the body. The sticker, about the size of a postage stamp, can be worn on the skin and is designed to pick up on signs of disease, such as liver and kidney failure and the progression of solid tumors.

In an open-access study appearing today in Science Advances, the team reports that the sensor can send sound waves through the skin and into the body, where the waves reflect off internal organs and back out to the sticker. The pattern of the reflected waves can be read as a signature of organ rigidity, which the sticker can measure and track.

“When some organs undergo disease, they can stiffen over time,” says the senior author of the paper, Xuanhe Zhao, professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. “With this wearable sticker, we can continuously monitor changes in rigidity over long periods of time, which is crucially important for early diagnosis of internal organ failure.”

The team has demonstrated that the sticker can continuously monitor the stiffness of organs over 48 hours and detect subtle changes that could signal the progression of disease. In preliminary experiments, the researchers found that the sticky sensor can detect early signs of acute liver failure in rats.

The engineers are working to adapt the design for use in humans. They envision that the sticker could be used in intensive care units (ICUs), where the low-profile sensors could continuously monitor patients who are recovering from organ transplants.

“We imagine that, just after a liver or kidney transplant, we could adhere this sticker to a patient and observe how the rigidity of the organ changes over days,” lead author Hsiao-Chuan Liu says. “If there is any early diagnosis of acute liver failure, doctors can immediately take action instead of waiting until the condition becomes severe.” Liu was a visiting scientist at MIT at the time of the study and is currently an assistant professor at the University of Southern California.

The study’s MIT co-authors include Xiaoyu Chen and Chonghe Wang, along with collaborators at USC.

Sensing wobbles

Like our muscles, the tissues and organs in our body stiffen as we age. With certain diseases, stiffening organs can become more pronounced, signaling a potentially precipitous health decline. Clinicians currently have ways to measure the stiffness of organs such as the kidneys and liver using ultrasound elastography — a technique similar to ultrasound imaging, in which a technician manipulates a handheld probe or wand over the skin. The probe sends sound waves through the body, which cause internal organs to vibrate slightly and send waves out in return. The probe senses an organ’s induced vibrations, and the pattern of the vibrations can be translated into how wobbly or stiff the organ must be.

Ultrasound elastography is typically used in the ICU to monitor patients who have recently undergone an organ transplant. Technicians periodically check in on a patient shortly after surgery to quickly probe the new organ and look for signs of stiffening and potential acute failure or rejection.

“After organ transplantation, the first 72 hours is most crucial in the ICU,” says another senior author, Qifa Zhou, a professor at USC. “With traditional ultrasound, you need to hold a probe to the body. But you can’t do this continuously over the long term. Doctors might miss a crucial moment and realize too late that the organ is failing.”

The team realized that they might be able to provide a more continuous, wearable alternative. Their solution expands on an ultrasound sticker they previously developed to image deep tissues and organs.

“Our imaging sticker picked up on longitudinal waves, whereas this time we wanted to pick up shear waves, which will tell you the rigidity of the organ,” Zhao explains.

Existing ultrasound elastrography probes measure shear waves, or an organ’s vibration in response to sonic impulses. The faster a shear wave travels in the organ, the stiffer the organ is interpreted to be. (Think of the bounce-back of a water balloon compared to a soccer ball.)

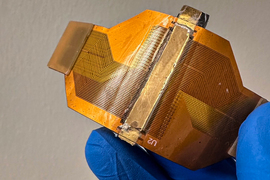

The team looked to miniaturize ultrasound elastography to fit on a stamp-sized sticker. They also aimed to retain the same sensitivity of commercial hand-held probes, which typically incorporate about 128 piezoelectric transducers, each of which transforms an incoming electric field into outgoing sound waves.

“We used advanced fabrication techniques to cut small transducers from high-quality piezoelectric materials that allowed us to design miniaturized ultrasound stickers,” Zhou says.

The researchers precisely fabricated 128 miniature transducers that they incorporated onto a 25-millimeter-square chip. They lined the chip’s underside with an adhesive made from hydrogel — a sticky and stretchy material that is a mixture of water and polymer, which allows sound waves to travel into and out of the device almost without loss.

In preliminary experiments, the team tested the stiffness-sensing sticker in rats. They found that the stickers were able to take continuous measurements of liver stiffness over 48 hours. From the sticker’s collected data, the researchers observed clear and early signs of acute liver failure, which they later confirmed with tissue samples.

“Once liver goes into failure, the organ will increase in rigidity by multiple times,” Liu notes.

“You can go from a healthy liver as wobbly as a soft-boiled egg, to a diseased liver that is more like a hard-boiled egg,” Zhao adds. “And this sticker can pick up on those differences deep inside the body and provide an alert when organ failure occurs.”

The team is working with clinicians to adapt the sticker for use in patients recovering from organ transplants in the ICU. In that scenario, they don’t anticipate much change to the sticker’s current design, as it can be stuck to a patient’s skin, and any sound waves that it sends and receives can be delivered and collected by electronics that connect to the sticker, similar to electrodes and EKG machines in a doctor’s office.

“The real beauty of this system is that since it is now wearable, it would allow low-weight, conformable, and sustained monitoring over time,” says Shrike Zhang, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and associate bioengineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “This would likely not only allow patients to suffer less while achieving prolonged, almost real-time monitoring of their disease progression, but also free trained hospital personnel to other important tasks.”

The researchers are also hoping to work the sticker into a more portable, self-enclosed version, where all its accompanying electronics and processing is miniaturized to fit into a slightly larger patch. Then, they envision that the sticker could be worn by patients at home, to continuously monitor conditions over longer periods, such as the progression of solid tumors, which are known to harden with severity.

“We believe this is a life-saving technology platform,” Zhao says. “In the future, we think that people can adhere a few stickers to their body to measure many vital signals, and image and track the health of major organs in the body.”

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health.