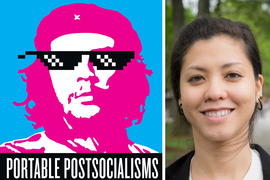

As a state run by a Communist Party, Cuba appears set apart from many of its neighbors in the Americas. One thing lost as a result, to a large extent, is a nuanced understanding of the perspectives of Cuban citizens. MIT’s Paloma Duong, an associate professor in the program in Comparative Media Studies/Writing, has helped fill this void with a new book that closely examines contemporary media — especially online communities and music — to look at what Cubans think about the contemporary world and what outsiders think about Cuba. The book, “Portable Postsocialisms: New Cuban Mediascapes after the End of History,” has just been published by the University of Texas Press. MIT News spoke with Duong about her work.

Q: What is the book about?

A: The book looks at a specific moment in Cuban history, the first two decades of the 21st century, as a case study of the relationship between culture, politics, and emergent media technologies. This is a greater moment of access to the internet and digital media technologies. The 1990s are known as the “Special Period” in Cuba, a decade of economic collapse and disorientation. Yet while the turn of the 21st century is this moment of profound change, images of a Cuba frozen in time endure.

One of the book’s focal points is to delve into the cultural and political discourses of change and continuity produced in this new media context. What is this telling us about Cubans’ experience of postsocialism — that is, the moment when the old referents of socialism still exist in everyday experience but socialism as a radical project of social transformation no longer appears as a viable collective goal? And, in turn, what can this tell us about the more general global experience concerning the demise of and desire for socialist utopias in this time period?

That question also requires a look at how global narratives and images about Cuba circulate. The symbolic weight of Cuba as the last bastion of socialism, as inspiration or cautionary tale existing outside of historical time, is one of them. I examine Cuba as a traveling media object invested with competing political desires. Even during the Prohibition Era in the U.S. you can already hear and see Cuba as a provider of transgressive desires to the American imagination in songs and advertising from that time.

Top-down narratives are routinely imposed on Cubans, either by their own government or by foreign observers exoticizing Cubans. I wanted to understand how Cubans were narrating their own experience of change. But I also wanted to recognize the international impact of the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and account for how its global constituents experienced its denouement.

Q: The book looks at Cuban culture with reference to music, fashion, online communities, and more. Why did you decide to explore all these cultural artifacts?

A: Because I was looking at both Cubans’ accounts of postsocialism, and at Cuba as an object of imagination traveling around the world, it seemed to me impossible to just choose one medium. The way we construct our images of the world, and ourselves, is intrinsically multimedia. We don’t just get all our information from literature, or film, or news media alone. Instead, I focus on specific narratives and images of change — of womanhood, of economic reform, of Internet access, and so on — looking at how they are reproduced or contested across media practices and cultural objects.

I use the term “portable” in different ways to describe these operations. A song, for instance, can be portable in many ways. Digital and especially streaming media open new circuits of music exchange and consumption. But the aesthetic experience of a song is itself a portable one; it lingers and remains with you. And whether analyzing songs, advertising, memes, or more, I study objects and practices that allow us to see the double status of Cuba, as a symbol and as an experience.

In this sense the book is about Cuba, but it is also about ourselves. We tend to look at Cuba through a Cold War framework that casts the country as an exception with respect to former socialist countries, to Latin America, to the capitalist world. But what happens if we look at Cuba as [also] participating in that world, not as an exception but as a particular experience of broader transformations? I’m not saying Cuba is the same as everywhere else. But the premise of the book is that Cuba is not an exceptional place outside of history. In fact, I argue that the narrative of its exceptionality is the key to understanding our shared historical moment and the political dimensions of our cultural and media practices.

Q: How would you say this approach sits with reference to other studies of modern Cuba?

A: There are other, more traditional scholarly ways of looking at Cuba. Some perspectives emphasize the liberal individual confronting an authoritarian state, foregrounding repression and censorship. Others focus instead on the Cuban nation-state as resisting global markets and transnational capital.

There are merits to these perspectives. But when only those perspectives predominate we miss the ways in which both the state and markets might dispossess everyday citizens. In looking at the cultural responses of people, you see citizens picking up on the fact that the global markets are leaving them behind, that the state is leaving them behind. They are not getting either what the state promises, which is social welfare, or what the markets promise, which is upward mobility. The book shows how abandoning Cold War frameworks of analysis, and how taking into account the ways in which cultural and media practices shape our political experiences, can offer a new understanding of Cuba but also of our own global present.