In February 2018, standing in front of local press and his high school’s leaders, student council president Tanner Bonner argued his case for a school walkout in response to the recent Parkland shooting. On behalf of his fellow students, Bonner wanted to organize a day dedicated to speaking about gun violence and mental health. The school was initially resistant, but after multiple meetings with school administrators, he managed to organize and facilitate the event. The experience made him realize the importance of speaking up to create change.

“If you really see something and you have an idea of how you can put it together, you should go for it. We should encourage students to lift their voices when talking about issues that affect them,” he says.

Growing up in Dearborn Heights, Michigan, Bonner deeply valued his support systems, including his family and his high school English teachers. He was involved in numerous community programs, including band, theater, and student council.

Now a senior at MIT studying urban science and planning with computer science, Bonner is constantly looking for ways to build up the communities around him, working to provide equitable opportunities for all.

“I love to think about systems and society, and how we work together and make the best use of what we have, to ensure what we have is given equitably,” he says.

Bonner’s interest in urban science and planning stems from his love of math, specifically looking at how specific datasets apply to real-world issues. During his studies he has realized the importance of making data accessible for different audiences, and discovered the power of framing data to control a story line, especially in the context of health care accessibility. He aims to explore this idea further in his senior thesis.

“A headline doesn’t tell an entire story, nor does any single graph,” he says. “Different presentations of the same data alter our perception. The ideas that are drawn from such presentations can have substantial implications, and thus data must be carefully handled — especially data pertaining to people.”

In the spring of his first year at MIT, Bonner undertook a research project in the Research Laboratory of Electronics, where he was trained to label various speech cues, such as articulating vowels and consonants, using Praat software. The goal of the project was to enhance speech-recognition algorithms from speech signals gathered into a large data set. The experience, Bonner’s first hands-on research opportunity, allowed him to learn specifics of computer algorithms while also producing new data.

At the same time, Bonner was selected to attend 1vyG, the largest conference in the world for first-generation, low-income students. He describes the experience as not only eye-opening, but also validating, in that he found a community of people who shared similar experiences growing up low-income. “They could see me, and I could see them,” he says.

Upon returning from the conference, Bonner immediately began working with what was then called the First Generation Program at MIT. He started asking himself questions like, “What could other students benefit from that would have helped me as a first-year?” While he planned FLIPOP, a preorientation program for incoming students, he was also working with Class Awareness Support and Equality (CASE), a group on campus advocating on behalf of low-income students, and with the QuestBridge scholarship program.

Quickly, Bonner realized the overlap between these three groups, seeing that they could work together holistically to benefit first-generation and/or low-income students. With this in mind, he began reaching out to board members from each group in an attempt to plan joint events.

However, before anything could happen, the pandemic struck.

Since the groups could not meet in person, they started working together over Zoom, eventually working with administrators to develop a comprehensive Covid-19 undergraduate response document, published or shared through mailing lists and social media, containing information about where student could find resources during the pandemic.

“It made me realize we can accomplish something really big together,” he says.

In the fall semester of his junior year, Bonner partnered with fellow student Eleane Lema to officially bring all three organizations together, creating the First Generation and/or Low-Income Program, also known as FLI@MIT.

The organization contained committees with smaller subcommittees, as a way to make it easier for anyone to join, without a strenuous time commitment. It now encompasses more than 30 student volunteers, all working to advocate for low-income and/or first-generation students.

“Everyone has their own unique experience, yet we share commonalities in hardships and barriers that it makes it so important that we have a space to get together,” Bonner says.

In his academic studies, Bonner is currently working on a thesis to understand access barriers to mental health care in his home state of Michigan, specifically focusing on the metro Detroit area. He plans on investigating the distribution of health care services within the city and how those services might be unavailable or inaccessible to more vulnerable communities, especially during the pandemic. “Mental health is equally as important as physical health, though it is not always treated as such,” he says.

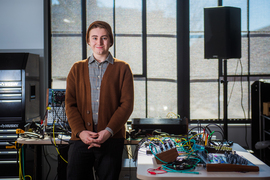

In addition to advocacy work, Bonner is also passionate about art — specifically theater, music, and dance — as an outlet both inside and outside of an academic setting. He is currently taking digital instrument design, which he considers a very exciting class. “It feels like bringing together music theory I’ve learned and computer science classes I’ve had. The aspects of sound design, musical interfaces, and performance are all very cool to me,” he says. Bonner has also been a member of DanceTroupe for four years and even helped orchestrate a Zoom performance last year.

“Art is a critical medium in today’s culture to talk about things where you might be considered breaking ice,” he says.

Looking ahead, Bonner hopes to attend graduate school to study city planning. He also plans to continue advocating for first-generation and low-income students, and encouraging undergraduate and graduate students to collaborate more actively, sharing resources, experiences, and advice.