Black holes are invisible by nature. Their pull is inescapable, forever trapping any light that falls into their gravitational abyss. But just beyond a black hole’s point of no return, light persists, and its patterns, like a photo negative, can reveal a black hole’s lurking presence.

Now an international team of astronomers, including researchers at MIT’s Haystack Observatory, has captured the light around our own supermassive black hole, revealing for the first time, an image of Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*, pronounced ‘sadge-ay-star’), the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy.

The image was created by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) — a global network of radio telescopes whose movements are choreographed so they function as one virtual, planet-sized telescope. The researchers focused the EHT array on the center of our galaxy, 27,000 light years from Earth, cutting through our planet’s atmosphere and the turbulent plasma beyond our solar system.

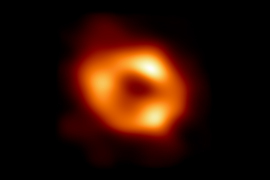

The resulting image reveals Sgr A* for the first time, in the form of a glowing, donut-shaped ring of light. This ring structure lies just outside the event horizon, or the point beyond which light cannot escape, and is the result of light being bent by the black hole’s enormous gravity. The bright ring encircles a dark center, described as the black hole’s “shadow.”

The ring’s white-hot plasma is estimated to be 10 billion Kelvin, or 18 billion degrees Fahrenheit. Judging from the ring’s dimensions, Sgr A* is roughly 4 million times the mass of the sun and incredibly compact, with a size that could fit within the orbit of Venus.

The image is the first visual confirmation that a black hole indeed exists at the center of our galaxy. Astronomers previously have observed stars circling around an invisible, massive, and extremely dense object — all signs pointing to a supermassive black hole. The image revealed today provides the first visual evidence that the object is a black hole, with dimensions that agree with predictions based on Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

“It is notoriously difficult to reconstruct images from a widely dispersed array like the EHT, and both rigor and ingenuity have been required to properly understand and quantify uncertainties,” says Colin Lonsdale, director of MIT’s Haystack Observatory. “The result is a milestone in our understanding of black holes in general and the one at the center of our galaxy in particular.”

The image and accompanying analyses are presented today in a number of papers appearing in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The findings are the result of work by more than 300 researchers from 80 institutions, including MIT, which together make up the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

Chasing a black hole’s tail

The new image of Sgr A* follows the first-ever image of a black hole, which was obtained by the EHT in 2019. That groundbreaking image was of M87*, the supermassive black hole at the center of Messier 87, a galaxy located 53 million light years from Earth.

M87* is a goliath compared to Sgr A*, with a mass of 6.5 billion suns (more than 1,000 times heavier than our own black hole), and a size that could easily swallow the entire solar system. And yet the image of M87* reveals a bright ring structure, much like Sgr A*. The similarity between the two images confirms another prediction of general relativity: that all black holes are alike, no matter their size.

“We now have a consistent image that looks like general relativity is working on both ends of supermassive black holes,” says EHT collaboration member Kazunori Akiyama, a research scientist at MIT’s Haystack Observatory.

The images of both black holes are based on data taken by the EHT of the respective sources in 2017. However, it took far more time and effort to bring Sgr A* into focus, due to its smaller size and its location within our own galaxy.

Astronomers suspect that hot gas circles both black holes at the same velocity, close to the speed of light. As Sgr A* is 1,500 times smaller than M87*, its speeding light is much harder to resolve. (Similarly, it’s harder to photograph a dog chasing its tail than one running at the same speed around a large park.)

The fact that Sgr A* lies in our own galaxy also presented an imaging challenge. M87* sits in a galaxy that is offset from our own, making it easier to see. In contrast, Sgr A* lies at the center of our own galactic plane, which hosts pockets of heated gas, or turbulent plasma, that can distort any emissions from the black hole that reach the Earth.

“It’s like trying to see through a jet engine’s blowing warm air,” Akiyama says. “It was very complicated, and that was why this image took longer to resolve.”

Jumping data

To capture a clear image of Sgr A*, astronomers coordinated eight radio observatories around the world to act as one virtual telescope, which they pointed at the center of the Milky Way over several days in April 2017. Each observatory recorded incoming light data using high-speed recorders developed at Haystack Observatory. These recorders were designed to process an enormous amount of data at rates of 4 gigabytes per second.

After collecting a total of 5 petabytes of data, encompassing observations of both Sgr A* and M87*, hard drives full of recorded data were shipped, half to Haystack, and the other half to the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany. Both locations house correlators — massive supercomputers that worked to “correlate” the data, comparing the data streams between different observatories, and converting that data into signals that a planet-sized telescope would see.

They then calibrated the data — a meticulous process of weeding out noise from sources such as instrumentation effects and the Earth’s own atmosphere, to effectively focus the virtual telescope’s “mirror” on signals specific to Sgr A*.

Then imaging teams took on the task of translating the signals into a representative image of the black hole — a far trickier challenge than imaging M87*, which was a larger, steadier source, changing very little over several days.

“Sgr A* is changing over minutes, so the data is jumping all over the place,” says EHT collaboration member Vincent Fish, a research scientist at Haystack. “That’s the fundamental challenge in imaging this black hole.”

Akiyama, who led the EHT’s imaging team, developed a new algorithm to pair with those used to image M87*. The researchers fed data into each algorithm to generate thousands of images of the black hole. They averaged these images to generate one main image, which revealed Sgr A* as a glowing, ring-like structure.

In coming years, the scientists expect to collect more data of Sgr A* and other black holes as the EHT expands, adding more telescopes to its virtual array.

“The techniques developed for Sgr A* pave the way for spectacular EHT images and science to come, as the telescope array is expanded and refined,” Lonsdale says.

“The next step is, can we get sharper images of this ring?” Akiyama says. “Now we can only see the brightest features. We want to also capture fainter substructures. Then we expect to see something more detailed, and different from that first donut.”

The Haystack EHT team also includes John Barrett, Roger Cappallo, Geoff Crew, Joseph Crowley, Mark Derome, Kevin Dudevoir, Michael Hecht, Dan Hoak, Lynn Matthews, Kotaro Moriyama, Violet Pfeiffer, Michael Poirier, Alan Rogers, Chester Ruszczyk, Jason SooHoo, Don Sousa, Michael Titus, and Alan Whitney. Additional contributors were James Moran and MIT alumni Daniel Palumbo, Katie Bouman, Lindy Blackburn, Sera Markoff, and Bill Freeman, a professor in MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.