The first scientific analysis of images taken by NASA’s Perseverance rover has now confirmed that Mars’ Jezero crater — which today is a dry, wind-eroded depression — was once a quiet lake, fed steadily by a small river some 3.7 billion years ago.

The images also reveal evidence that the crater endured flash floods. This flooding was energetic enough to sweep up large boulders from tens of miles upstream and deposit them into the lakebed, where the massive rocks lie today.

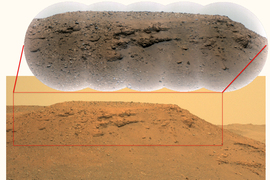

The new analysis, published today in the journal Science, is based on images of the outcropping rocks inside the crater on its western side. Satellites had previously shown that this outcrop, seen from above, resembled river deltas on Earth, where layers of sediment are deposited in the shape of a fan as the river feeds into a lake.

Perseverance’s new images, taken from inside the crater, confirm that this outcrop was indeed a river delta. Based on the sedimentary layers in the outcrop, it appears that the river delta fed into a lake that was calm for much of its existence, until a dramatic shift in climate triggered episodic flooding at or toward the end of the lake’s history.

“If you look at these images, you’re basically staring at this epic desert landscape. It’s the most forlorn place you could ever visit,” says Benjamin Weiss, professor of planetary sciences in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and a member of the analysis team. “There’s not a drop of water anywhere, and yet, here we have evidence of a very different past. Something very profound happened in the planet’s history.”

As the rover explores the crater, scientists hope to uncover more clues to its climatic evolution. Now that they have confirmed the crater was once a lake environment, they believe its sediments could hold traces of ancient aqueous life. In its mission going forward, Perseverance will look for locations to collect and preserve sediments. These samples will eventually be returned to Earth, where scientists can probe them for Martian biosignatures.

“We now have the opportunity to look for fossils,” says team member Tanja Bosak, professor of geobiology at MIT. “It will take some time to get to the rocks that we really hope to sample for signs of life. So, it’s a marathon, with a lot of potential.”

Tilted beds

On Feb. 18, 2021, the Perseverance rover landed on the floor of Jezero crater, a little more than a mile away from its western fan-shaped outcrop. In the first three months, the vehicle remained stationary as NASA engineers performed remote checks of the rover’s many instruments.

During this time, two of Perseverance’s cameras, Mastcam-Z and the SuperCam Remote Micro-Imager (RMI), captured images of their surroundings, including long-distance photos of the outcrop’s edge and a formation known as Kodiak butte, a smaller outcop that planetary geologists surmise may have once been connected to the main fan-shaped outcrop but has since partially eroded.

Once the rover downlinked images to Earth, NASA’s Perseverance science team processed and combined the images, and were able to observe distinct beds of sediment along Kodiak butte in surprisingly high resolution. The researchers measured each layer’s thickness, slope, and lateral extent, finding that the sediment must have been deposited by flowing water into a lake, rather than by wind, sheet-like floods, or other geologic processes.

The rover also captured similar tilted sediment beds along the main outcrop. These images, together with those of Kodiak, confirm that the fan-shaped formation was indeed an ancient delta and that this delta fed into an ancient Martian lake.

“Without driving anywhere, the rover was able to solve one of the big unknowns, which was that this crater was once a lake,” Weiss says. “Until we actually landed there and confirmed it was a lake, it was always a question.”

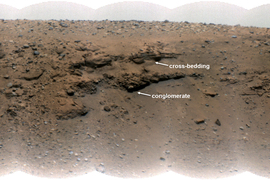

Boulder flow

When the researchers took a closer look at images of the main outcrop, they noticed large boulders and cobbles embedded in the youngest, topmost layers of the delta. Some boulders measured as wide as 1 meter across, and were estimated to weigh up to several tons. These massive rocks, the team concluded, must have come from outside the crater, and was likely part of bedrock located on the crater rim or else 40 or more miles upstream.

Judging from their current location and dimensions, the team says the boulders were carried downstream and into the lakebed by a flash-flood that flowed up to 9 meters per second and moved up to 3,000 cubic meters of water per second.

“You need energetic flood conditions to carry rocks that big and heavy,” Weiss says. “It’s a special thing that may be indicative of a fundamental change in the local hydrology or perhaps the regional climate on Mars.”

Because the huge rocks lie in the upper layers of the delta, they represent the most recently deposited material. The boulders sit atop layers of older, much finer sediment. This stratification, the researchers say, indicates that for much of its existence, the ancient lake was filled by a gently flowing river. Fine sediments — and possibly organic material — drifted down the river, and settled into a gradual, sloping delta.

However, the crater later experienced sudden flash floods that deposited large boulders onto the delta. Once the lake dried up, and over billions of years wind eroded the landscape, leaving the crater we see today.

The cause of this climate turnaround is unknown, although Weiss says the delta’s boulders may hold some answers.

“The most surprising thing that’s come out of these images is the potential opportunity to catch the time when this crater transitioned from an Earth-like habitable environment, to this desolate landscape wasteland we see now,” he says. “These boulder beds may be records of this transition, and we haven’t seen this in other places on Mars.”

This research was supported, in part, by NASA.