Several years ago, MIT neuroscientists showed that they could dramatically reduce the amyloid plaques seen in mice with Alzheimer’s disease simply by exposing the animals to light flickering at a specific frequency.

In a new study, the researchers have found that this treatment has widespread effects at the cellular level, and it helps not just neurons but also immune cells called microglia. Overall, these effects reduce inflammation, enhance synaptic function, and protect against cell death, in mice that are genetically programmed to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

“It seems that neurodegeneration is largely prevented,” says Li-Huei Tsai, the director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and the senior author of the study.

The researchers also found that the flickering light boosted cognitive function in the mice, which performed much better on tests of spatial memory than untreated mice did. The treatment also produced beneficial effects on spatial memory in older, healthy mice.

Chinnakkaruppan Adaikkan, an MIT postdoc, is the lead author of the study, which appears online in Neuron on May 7.

Beneficial brain waves

Tsai’s original study on the effects of flickering light showed that visual stimulation at a frequency of 40 hertz (cycles per second) induces brain waves known as gamma oscillations in the visual cortex. These brain waves are believed to contribute to normal brain functions such as attention and memory, and previous studies have suggested that they are impaired in Alzheimer’s patients.

Tsai and her colleagues later found that combining the flickering light with sound stimuli — 40-hertz tones — reduced plaques even further and also had farther-reaching effects, extending to the hippocampus and parts of the prefrontal cortex. The researchers have also found cognitive benefits from both the light- and sound-induced gamma oscillations.

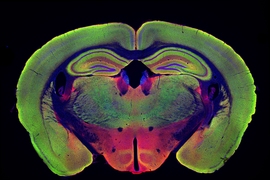

In their new study, the researchers wanted to delve deeper into how these beneficial effects arise. They focused on two different strains of mice that are genetically programmed to develop Alzheimer’s symptoms. One, known as Tau P301S, has a mutated version of the Tau protein, which forms neurofibrillary tangles like those seen in Alzheimer’s patients. The other, known as CK-p25, can be induced to produce a protein called p25, which causes severe neurodegeneration. Both of these models show much greater neuron loss than the model they used for the original light flickering study, Tsai says.

The researchers found that visual stimulation, given one hour a day for three to six weeks, had dramatic effects on neuron degeneration. They started the treatments shortly before degeneration would have been expected to begin, in both types of Alzheimer’s models. After three weeks of treatment, Tau P301S mice showed no neuronal degeneration, while the untreated Tau P301S mice had lost 15 to 20 percent of their neurons. Neurodegeneration was also prevented in the CK-p25 mice, which were treated for six weeks.

“I have been working with p25 protein for over 20 years, and I know this is a very neurotoxic protein. We found that the p25 transgene expression levels are exactly the same in treated and untreated mice, but there is no neurodegeneration in the treated mice,” Tsai says. “I haven’t seen anything like that. It’s very shocking.”

The researchers also found that the treated mice performed better in a test of spatial memory called the Morris water maze. Intriguingly, they also found that the treatment improved performance in older mice that did not have a predisposition for Alzheimer’s disease, but not young, healthy mice.

Genetic changes

To try to figure out what was happening at a cellular level, the researchers analyzed the changes in gene expression that occurred in treated and untreated mice, in both neurons and microglia — immune cells that are responsible for clearing debris from the brain.

In the neurons of untreated mice, the researchers saw a drop in the expression of genes associated with DNA repair, synaptic function, and a cellular process called vesicle trafficking, which is important for synapses to function correctly. However, the treated mice showed much higher expression of those genes than the untreated mice. The researchers also found higher numbers of synapses in the treated mice, as well as a greater degree of coherence (a measure of brain wave synchrony between different parts of the brain).

In their analysis of microglia, the researchers found that cells in untreated mice turned up their expression of inflammation-promoting genes, but the treated mice showed a striking decrease in those genes, along with a boost of genes associated with motility. This suggests that in the treated mice, microglia may be doing a better job of fighting off inflammation and clearing out molecules that could lead to the formation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the researchers say. They also found lower levels of the version of the Tau protein that tends to form tangles.

A key unanswered question, which the researchers are now investigating, is how gamma oscillations trigger all of these protective measures, Tsai says.

“A lot of people have been asking me whether the microglia are the most important cell type in this beneficial effect, but to be honest, we really don’t know,” she says. “After all, oscillations are initiated by neurons, and I still like to think that they are the master regulators. I think the oscillation itself must trigger some intracellular events, right inside neurons, and somehow they are protected.”

The researchers also plan to test the treatment in mice with more advanced symptoms, to see if neuronal degeneration can be reversed after it begins. They have also begun phase 1 clinical trials of light and sound stimulation in human patients.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Halis Family Foundation, the JPB Foundation, and the Robert A. and Renee E. Belfer Family Foundation.

![“…[I]f humans behave similarly to mice in response to this treatment, I would say the potential is just enormous, because it’s so noninvasive, and it’s so accessible,” says Li-Huei Tsai, the Picower Professor of Neuroscience, when describing a new treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.](/sites/default/files/styles/news_article__archive/public/images/201612/MIT-li-huei-tsai.jpg?itok=jrC2K2AI)