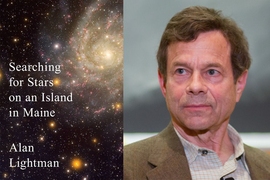

A few years ago MIT scholar Alan Lightman was lying in a boat off the coast of Maine, staring at the stars, when he felt as if he were “becoming a part of something far larger than himself.” This moment, which he calls a “transcendent experience,” gave him a greater appreciation for the allure of the ethereal and the permanent. But Lightman remains a scientist, committed to the material world, so he decided to write about that tension. The result is a new book, “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine,” published by Pantheon, which is an extended essay on science, religion, and knowledge. Lightman, a trained theoretical physicist and senior lecturer in physics, as well as a professor of the practice of the humanities at the Institute, recently talked with MIT News about his new work.

Q: What is your new book about?

A: Well, it’s generally about science and religion. More specifically, it’s about the different kinds of knowledge that are had in science and religion, and the differences in the way that knowledge is obtained. When I’m talking about religion, I’m mainly not talking about organized, institutional religion, but the personal religious experience, or what one might call the transcendent experience. I draw on recent scientific developments to discuss the way science has rendered everything in the physical universe impermanent, which strikes at many of the beliefs of religious doctrine. But I also draw on philosophers and theologians and writers, from Aristotle to St. Augustine to Emily Dickinson. Because these are weighty issues, I don’t confront them head-on, in a didactic manner. The book is written in the style of an extended meditation, in the vein of Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” or Annie Dillard’s “Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.” So, it has that kind of meandering tone that is rooted in a geographical place. In this case it’s an island in Maine.

Q: You draw out a distinction in the book between “absolute” and “relative” forms of knowledge, as a way of thinking about the differences between science and religion — and even about the tensions within science. Could you explain this distinction?

A: The conversation between science and religion is is embedded in a larger conversation about what I call the “absolutes” versus the “relatives.” The absolutes are qualities including permanence, immortality, unity, certainty — all qualities religious belief rewards us with. And I think we have a deep psychological yearning for those qualities. And the relatives are the converse of that: Impermanence, fragmentation, mortality, materiality, divisibility — qualities that have been found by science to exist in the material world.

We once thought the atom was indivisible and indestructible, and science has shown the atom can be split, and even its component parts can be split, and we don’t know where the splitting will end. Stars, which were considered to be permanent and even divine, have been shown by modern science to be just [objects] which will exhaust their nuclear fuel and burn out. Even the entire universe was once thought to be the largest unity possible, but leading scientists [suggest] our universe is just one of many universes out there, the multiverse. Of course there’s also Einstein’s relativity, that even motion and time are not absolute either. If you found all your absolutes have been negated, is there still anything to hold on to, if you long for permanence and unity? To me that’s a larger framework in which to discuss science and religion.

Our longing for absolutes is so strong that even within the sciences we believe in certain absolutes, which are beliefs that cannot be proven. The most important absolute in science, which I call the central doctrine of science, is the belief that nature is lawful, and that those laws hold true everywhere and all the time. Many scientists also believe there is a final theory of nature. In principle you could calculate any phenomena to infinite accuracy with a final theory. The irony there is that even if we found it, we wouldn’t know that we had found it, because you can never be certain that tomorrow there would not be some phenomena that violated your theory.

Q: To what extent do these transcendent experiences, such as losing yourself in wonder as you gaze at the stars, help generate the more strictly intellectual inquiry of the book?

A: With the particular subject matter of this book, about how does one balance spirituality and materiality, if you haven’t had the spiritual experience, you could not write about it with any authority. I think everybody has had transcendent experiences, where you feel at least briefly that you are connected to something much larger than yourelf. I don’t think you have to be on an island in Maine or in a boat looking up at the stars to have experiences like that. That can happen anywhere, as long as you’ve got a quiet moment. Because most of my life has been spent as a scientist, it would be very easy to be condescending toward the spiritual dimension of the world. I wanted to show that I do understand that — whether I’m a believer or an atheist, I have felt it myself.