For certain frequencies of short-wave infrared light, most biological tissues are nearly as transparent as glass. Now, researchers have made tiny particles that can be injected into the body, where they emit those penetrating frequencies. The advance may provide a new way of making detailed images of internal body structures such as fine networks of blood vessels.

The new findings, based on the use of light-emitting particles called quantum dots, is described in a paper in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering, by MIT research scientist Oliver Bruns, recent graduate Thomas Bischof PhD ’15, professor of chemistry Moungi Bawendi, and 21 others.

Near-infrared imaging for research on biological tissues, with wavelengths between 700 and 900 nanometers (billionths of a meter), is widely used, but wavelengths of around 1,000 to 2,000 nanometers have the potential to provide even better results, because body tissues are more transparent to that light. “We knew that this imaging mode would be better” than existing methods, Bruns explains, “but we were lacking high-quality emitters” — that is, light-emitting materials that could produce these precise wavelengths.

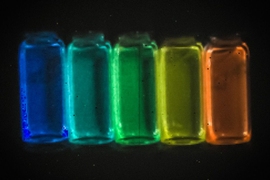

Light-emitting particles have been a specialty of Bawendi, the Lester Wolf Professor of Chemistry, whose lab has over the years developed new ways of making quantum dots. These nanocrystals, made of semiconductor materials, emit light whose frequency can be precisely tuned by controlling the exact size and composition of the particles.

The key was to develop versions of these quantum dots whose emissions matched the desired short-wave infrared frequencies and were bright enough to then be easily detected through the surrounding skin and muscle tissues. The team succeeded in making particles that are “orders of magnitude better than previous materials, and that allow unprecedented detail in biological imaging,” Bruns says. The synthesis of these new particles was initially described in a paper by graduate student Daniel Franke and others from the Bawendi group in Nature Communications last year.

The quantum dots the team produced are so bright that their emissions can be captured with very short exposure times, he says. This makes it possible to produce not just single images but video that captures details of motion, such as the flow of blood, making it possible to distinguish between veins and arteries.

The new light-emitting particles are also the first that are bright enough to allow imaging of internal organs in mice that are awake and moving, as opposed to previous methods that required them to be anesthetized, Bruns says. Initial applications would be for preclinical research in animals, as the compounds contain some materials that are unlikely to be approved for use in humans. The researchers are also working on developing versions that would be safer for humans.

The method also relies on the use of a newly developed camera that is highly sensitive to this particular range of short-wave infrared light. The camera is a commercially developed product, Bruns says, but his team was the first customer for the camera’s specialized detector, made of indium-gallium-arsenide. Though this camera was developed for research purposes, these frequencies of infrared light are also used as a way of seeing through fog or smoke.

Not only can the new method determine the direction of blood flow, Bruns says, it is detailed enough to track individual blood cells within that flow. “We can track the flow in each and every capillary, at super high speed,” he says. “We can get a quantitative measure of flow, and we can do such flow measurements at very high resolution, over large areas.”

Such imaging could potentially be used, for example, to study how the blood flow pattern in a tumor changes as the tumor develops, which might lead to new ways of monitoring disease progression or responsiveness to a drug treatment. “This could give a good indication of how treatments are working that was not possible before,” he says.

“This is an exciting and potentially revolutionary development for small animal imaging,” says Guillermo Tearney, a professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in this work. “By using probes that are tuned to wavelengths further out in the short-wave near-infrared, the investigators overcome scattering, which is the major phenomenon” limiting such in vivo microscopy, he says.

“In so doing, simpler and less invasive interrogation methods can be utilized to understand structure and function in animal models, on both the organ and cellular level,” Tearney says. “I anticipate that these probes will have a major impact on the field of intravital [done with living subjects] imaging and bioscience research.”

The team included members from MIT’s departments of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering, Biological Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering, as well as from Harvard Medical School, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Raytheon Vision Systems, and University Medical Center in Hamburg, Germany. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the National Foundation for Cancer Research, the Warshaw Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research, the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research, the Army Research Office through the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies at MIT, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the National Science Foundation.